Between the founding of Jamestown (1607) and the signing of the Declaration of Independence (1776), scattered English settlements grew into a group of colonies ready to declare themselves a nation. The colonists changed from thinking and acting as Englishmen to full awareness of themselves as Americans. During this time almost all writing was devoted to spiritual concerns and to practical matters of politics and promotion of settlements. In New England, fiction was considered sinful and little poetry was written. A few interesting personal journals and diaries survive.

Bradford, William (1590-1657), historian--'History of Plimoth Plantation'. Bradstreet, Anne (1612?-72), poet--'The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America'; 'Contemplations'. Byrd, William (1674-1744), historian and diarist--'History of the Dividing Line'; 'Secret Diary'. Edwards, Jonathan (1703-58), theologian--'Personal Narrative'; 'The Freedom of the Will'. Knight, Sarah Kemble (1666-1727), diarist--'The Journal of Mme. Knight'. Mather, Cotton (1663-1728), theologian--'Wonders of the Invisible World'; 'Magnalia Christi Americana'. Rowlandson, Mary (1635?-78?), essayist--'A Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson'. Sewall, Samuel (1652-1730), diarist--'Diary of Samuel Sewall 1674-1729'; 'The Selling of Joseph'. Smith, John (1580-1631), historian--'A Description of New England'; 'The General History of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles'. Taylor, Edward (1642-1729), poet--'God's Determinations'; 'Sacramental Meditations'. Ward, Nathaniel (1578?-1652), essayist--'The Simple Cobler of Aggawam'. Wigglesworth, Michael (1631-1705), poet--'The Day of Doom'. Williams, Roger (1603?-83), historian--'A Key into the Language of America'; 'The Bloody Tenet of Persecution'.

a 0 A

The Shaping of a New Nation

American writing in colonial days, as has been seen, dealt largely with religion. In the last 30 years of the 18th century, however, men turned their attention from religion to the subject of government. These were the years when the colonies broke away from England and declared themselves a new and independent nation. It was a great decision for Americans to make. Feeling ran high, and people expressed their opinions in a body of writing that, if not literature in the narrow sense, is certainly literature in the sense of its being great writing.

Since World War II, moves for national independence have been numerous throughout the world. Historically, however, the first people to throw off a colonial yoke and establish a free society were those of the American Colonies. The literary record of their struggle thus is a fascinating and inspiring story to people everywhere.

Franklin--Spokesman for a Nation

The birth of the United States was witnessed by Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) in his last years. His career began in colonial days. At 17 he ran away from his home in Boston and went to Philadelphia. How he took up printing, made enough money to retire at 42, and educated himself is the subject of his 'Autobiography', first published in book form in English in 1793. This is the first and most celebrated story of the American self-made man. Many of his rules for self-improvement ("Early to bed, early to rise," and so forth) appeared in his 'Poor Richard's Almanack', first published in 1732.

Franklin was simple in manners and tastes. When he represented the colonies in the European courts, he insisted on wearing the simple homespun of colonial dress. He used the plain speech of the provincial people. He displayed the practical turn of mind of a people who had shrewdly conquered a wilderness.

Franklin embodied the American idea. That idea was defined by Michel Guillaume St. Jean de Crevecoeur (1735-1813), a Frenchman who lived in America for many years before the Revolution. In his 'Letters from an American Farmer' (1782) he described the colonists as happy compared with the suffering people of Europe. In one letter he asked, "What then is the American, this new man?" This is a challenging question even today, nearly 200 years later. Crevecoeur's answer then was:

"He is an American, who, leaving behind him all his ancient prejudices and manners, receives new ones from the new mode of life he has embraced, the new government he obeys, and the new rank he holds. He becomes an American by being received in the broad lap of our great Alma Mater (nourishing mother). Here individuals of all nations are melted into a new race of men, whose labours and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world . . . . The American is a new man, who acts upon new principles; he must therefore entertain new ideas and form new opinions . . . . This is an American."

The immigrant prospered in America, and he became fiercely loyal to the system that made possible his prosperity. That system, which included a large measure of personal freedom, was threatened by the British. Americans tried to preserve it by peaceful means. When this became impossible, they chose to become a separate nation.

Thomas Paine Arouses the Patriots

The power of words to affect the course of history is clearly seen in the writings of Thomas Paine (1737-1809). The shooting had started at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, but for months there was no move to break away from England. Then, in January 1776, appeared Paine's pamphlet 'Common Sense'. In brilliant language, logical and passionate, yet so simple that all could understand, Paine argued in favor of declaring independence from Britain. The effect was electric.

By June the Continental Congress resolved to break away; and on July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence appeared. Paine continued his pamphleteering during the war in 'The Crisis', a series of 16 papers. The first one begins, "These are the times that try men's souls." George Washington said that without Paine's bold encouragement the American cause might have been lost.

The famous Declaration of Independence was largely the work of Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826). In justifying the American Revolution to the world he stated the political axioms on which the revolution was based, among them the proposition that "all men are created equal." This phrase is at the very heart of democracy.

After the war Americans, having rejected their rulers, were faced with the job of governing themselves. They attempted "to form a more perfect Union." The result was the Constitution. Although the United States has flourished under the system of government outlined in the Constitution, not all Americans favored adopting the new plan when it was proposed. In the great debate over adopting it, Alexander Hamilton (1755?-1804) and others wrote 85 essays, known as 'The Federalist' (1787-88), in support of the Constitution.

Poets during these years wrote patriotic verses on political themes. Some of the poems of John Trumbull (1750-1831) and Joel Barlow (1754-1812) are interesting, but in style they were imitative of English poetry. Novels too resembled those written of England. Susanna (Haswell) Rowson (1762-1824) wrote 'Charlotte Temple' (1791), a sentimental tale of a betrayed heroine. 'Wieland' (1798), by Charles Brockden Brown (1771-1810), is patterned after an English novel. This imitativeness is not surprising: writers were in the habit of writing like Englishmen.

More and more, however, authors wanted to write as Americans. They had won political independence; they now wanted literary independence. The poet Philip Freneau (1752-1832) pleaded for a native literature. So did Noah Webster (1758-1843). "Customs, habits, and language," he wrote, "should be national." He did his part by compiling 'The American Spelling Book' (1783) and his 'American Dictionary of the English Language' (1828). "Center," instead of "centre," and "honor," instead of "honour," are typical of Webster's "Americanized" spelling.

a 0 A

Representative Writers: THE SHAPING OF A NEW NATION

The great questions in the last years of the 18th century were political ones. Should the colonists declare independence from England? Once they had done so, how, they asked, should they govern themselves? The literature of political discussion and debate in these years is of high quality. Immediately following independence, writers also made efforts to develop a native literature. This is the period of beginning for poetry, fiction, and drama in the United States.

Adams, Abigail (1744-1818), epistolist--'Letters of Mrs. Adams'. Adams, John (1735-1826), president and epistolist--'Diary and Autobiography'; 'The Adams-Jefferson Letters'. Barlow, Joel (1754-1812), poet--'The Vision of Columbus' ('The Columbiad'); 'The Hasty Pudding'. Brown, Charles Brockden (1771-1810), novelist--'Wieland'; 'Edgar Huntly'; 'Jane Talbot'. Crevecoeur, Michel Guillaume St. Jean de (1735-1813), essayist--'Letters from an American Farmer'. Equiano, Oloudah (Gustavus Vassa) (1745-1801), prose writer--'The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Oloudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African'. Franklin, Benjamin (1706-90), prose writer--'Autobiography'; 'Poor Richard's Almanack'. Freneau, Philip (1752-1832), poet--'The Indian Burying-Ground'; 'The British Prison Ship'. Hamilton, Alexander (1755?-1804), essayist--'The Federalist' (coauthor). Hopkinson, Francis (1737-91), poet--'The Battle of the Kegs'. Jefferson, Thomas (1743-1826), historian--'Notes on the State of Virginia'. Paine, Thomas (1737-1809), political philosopher--'Common Sense'; 'The Crisis'; 'The Rights of Man'. Payne, John Howard (1791-1852), playwright--'Clari, or the Maid of Milan' (with song 'Home, Sweet Home'). Rowson, Susanna (Haswell) (1762-1824), novelist--'Charlotte Temple'; 'Rebecca'. Tecumseh (1768-1813), orator--'We All Belong to One Family'. Trumbull, John (1750-1831), poetic satirist--'M'Fingal'; 'Progress of Dullness'. Webster, Noah (1758-1843), lexicographer--'Spelling Book'; 'American Dictionary of the English Language'. Wheatley, Phillis (1753?-84), poet--'Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral'. Weems, Mason Locke (1759-1825), biographer--'The Life and Memorable Actions of George Washington'.

Literature of the Early Republic

It was one thing for writers to want to create a native American literature; it was quite another thing to know how to do it. For 50 years after the founding of the nation, authors patterned their work after the writings of Englishmen. William Cullen Bryant was known as the American Wordsworth; Washington Irving's essays resemble those of Addison and Steele; James Fenimore Cooper wrote novels like those of Scott. Although the form and style of these Americans were English, the content--character and especially setting--was American. Every American region was described by at least one prominent writer.

Frontier life in western Pennsylvania is pictured in 'Modern Chivalry' (1792-1815), written by a friend of James Madison and Philip Freneau, Hugh Henry Brackenridge (1748-1816). This episodic narrative, modeled on Miguel de Cervantes' 'Don Quixote', shows how people in the backcountry behaved politically under the new Constitution. Henry Adams called 'Modern Chivalry' a "more thoroughly American book than any written before 1833." American it is, in character, setting, and theme.

The beauties of New England's hills and forests were sung by William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878). 'Thanatopsis' (1817) and 'A Forest Hymn' (1825) show a reverence for nature. The English critic Matthew Arnold thought 'To a Waterfowl' (1818) the best short poem in the English language.

New York City and its environs were the province of Washington Irving (1783-1859). 'Salmagundi' (1807-8), which he coauthored, describes the city's fashionable life. 'A History of New York . . . by Diedrich Knickerbocker' (1809), an imaginary Dutch historian, is an amusing account of its history under Dutch rule.

Irving's masterpieces were his sketches 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow' and 'Rip Van Winkle', both published in 1820. These tales--the first of Ichabod Crane, a superstitious schoolmaster, the second of Rip, who sought refuge in the Catskills from his shrewish wife and slept for 20 years--are among the best-loved American stories. Irving's literary skill was appreciated in England too. There he was recognized as the first important American writer.

James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851) wrote more than 30 novels and many other works. He was an enormously popular writer, in Europe as well as at home. Of interest to readers today are his opinions on democracy. Reared on an estate near Cooperstown, N.Y., the writer had a patrician upbringing. When he criticized democracy, as in 'The American Democrat' (1838), he criticized the crudity he saw in the United States of Andrew Jackson. Yet he defended the American democratic system against attacks by European aristocrats.

In his day Cooper was best known as the author of the 'Leatherstocking Tales', five novels of frontier life--the first examples of a type of literature that would become extremely popular decades later. These stories of stirring adventure, such as 'The Last of the Mohicans' (1826) and 'The Deerslayer' (1841), feature Cooper's hero Natty Bumppo, the skillful, courageous, and valorous woodsman. This character embodied American traits and so to Europeans seemed to represent the New World.

The South too was portrayed in fiction in these years. 'Swallow Barn' (1832), by John Pendleton Kennedy (1795-1870), pictures life on a Virginia plantation. Later portrayals of life in the Old Dominion, in fiction and in motion pictures, often follow the idealized picture of Virginia given in 'Swallow Barn'. In South Carolina many adventure novels of frontier life, such as 'The Yemassee' (1835), came from the pen of William Gilmore Simms (1806-70), sometimes called the Cooper of the South.

Thus by 1835 American writers had made a notable start toward creating a new and independent national literature. In Scotland in 1820 Sydney Smith, a famous critic who wrote for the Edinburgh Review, had asked: "In the four quarters of the globe, who reads an American book?" Sensitive Americans, conscious of their cultural inferiority, winced at this slighting remark. More and more, however, they had reason to be proud of their writers. In the next 20 years American literature would come to the full flowering which had been hoped for since the Revolution.

a 0 A

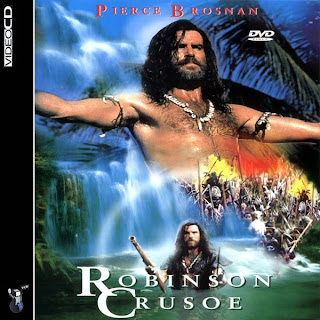

Activity: Film Viewing of “The Legend of the Sleepy Hollow”

The Author:

Washington Irving (1783-1859), American writer, the first American author to achieve international renown, who created the fictional characters Rip Van Winkle and Ichabod Crane. The critical acceptance and enduring popularity of Irving's tales involving these characters proved the effectiveness of the short story as an American literary form.

Born in New York City, Irving studied law at private schools. After serving in several law offices and traveling in Europe for his health from 1804 to 1806, he was eventually admitted to the bar in 1806. His interest in the law was neither deep nor long-lasting, however, and Irving began to contribute satirical essays and sketches to New York newspapers as early as 1802. A group of these pieces, written from 1802 to 1803 and collected under the title Letters of Jonathan Oldstyle, Gent., won Irving his earliest literary recognition. From 1807 to 1808 he was the leading figure in a social group that included his brothers William Irving and Peter Irving and William's brother-in-law James Kirke Paulding; together they wrote Salmagundi, or, the Whim-Whams and Opinions of Launcelot Langstaff, Esq., and Others, a series of satirical essays and poems on New York society. Irving's contributions to this miscellany established his reputation as an essayist and wit, and this reputation was enhanced by his next work, A History of New York (1809), ostensibly written by Irving's famous comic creation, the Dutch-American scholar Diedrich Knickerbocker. The work is a satirical account of New York State during the period of Dutch occupation (1609-1664); Irving's mocking tone and comical descriptions of early American life counterbalanced the nationalism prevalent in much American writing of the time. Generally considered the first important contribution to American comic literature, and a great popular success from the start, the work brought Irving considerable fame and financial reward.

In 1815 Irving went to Liverpool, England, as a silent partner in his brothers' commercial firm. When, after a series of losses, the business went into bankruptcy in 1818, Irving returned to writing for a living. In England he became the intimate friend of several leading men of letters, including Thomas Campbell, Sir Walter Scott, and Thomas Moore. Under the pen name of Geoffrey Crayon, Irving wrote the essays and short stories collected in The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. (1819-1820). The Sketch Book, as it is also known, was his most popular work and was widely acclaimed in both England and the United States for its geniality, grace, and humor. The collection's two most famous stories, both based on German folktales, are “Rip Van Winkle,” about a man who falls asleep in the woods for twenty years, and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” about a schoolteacher's encounter with a legendary headless horseman. Set in rural New York, these tales are considered classics in American literature.

From 1826 until 1829 Irving was a member of the staff of the United States legation in Madrid. During this period and after his return to England, he wrote several historical works, the most popular of which was the History of Christopher Columbus (1828). Another well-known work of this period was The Alhambra (1832), a series of sketches and stories based on Irving's residence in 1829 in an ancient Moorish palace at Granada, Spain. In 1832, after an absence that lasted 17 years, he returned to the United States, where he was welcomed as a figure of international importance. Over the next few years Irving traveled to the American West and wrote several books using the West as their setting. These works include A Tour on the Prairies (1835), Astoria (1836), and The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, U.S.A. (1837).

In 1842 Irving was appointed U.S. minister to Madrid, where he lived until 1846, continuing his historical research and writing. He returned to the United States again in 1846 and settled at Sunnyside, his country home near Tarrytown, New York, where he lived until his death. (Sunnyside is now a historic house and museum.) Irving's popular but elegant style, based on the styles of the British writers Joseph Addison and Oliver Goldsmith, and the ease and picturesque fancy of his best work attracted an international audience. To a certain extent his romantic attachment to Europe resulted in a thinness and overrefinement of material. Much of his work deals directly with English life and customs, and he never attempted to come to terms with the democratic American life of his time. On the other hand, American writers were encouraged by Irving's example to look beyond the United States for subject matter.

Irving's other works include Bracebridge Hall (1822), Tales of a Traveller (1824), A Chronicle of the Conquest of Granada (1829), Oliver Goldsmith (1849), and Life of Washington (5 volumes, 1855-1859).

Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2006. © 1993-2005 Microsoft Corporation.